This is one of my on-going issues. Where does functional, handmade pottery fit into the world these days? Do potters have to be artists? Do I?

Octavio Paz offers the clearest, most sensible distinction that I've seen yet, and adds industry as a third relevant category. He wrote an introductory article for the First World Crafts Exhibition in 1974, which I've read in In Praise of Hands, a 1974 book about the exhibition. So, not news, but new to me.

The rest of this post quotes his article, "Use and Contemplation".

"A vessel of baked clay: do not put it in a glass case alongside rare precious objects. It would look quite out of place. Its beauty is related to the liquid that it contains and to the thirst that it quenches. Its beauty is corporal: I see it, I touch it, I smell it, I hear it. If it is empty, it must be filled; if it is full , it must be emptied. I take it by the shaped handle as I would take a woman by the arm, I lift it up, I tip it over a pitcher into which I pour milk or pulque -- lunar liquids that open and close the doors of dawn and dark, waking and sleeping. Not an object to contemplate: an object to use. ...Handcrafts belong to a world antedating the separation of the useful and the beautiful." (In Praise of Hands, page 17)

"It is not simply its usefulness that makes the handcrafted object so captivating. It lives in intimate connivance with our senses and that is why it is so difficult to part company with it. It is like throwing an old friend out into the street." (page 19)

So art is to contemplate, and has no other use these days (well, a commercial one). Craft is to use and enjoy as sensory experience. Not quite; our contemplation of art is a sensory experience, and art pieces we are attracted to may become old friends, too. Not so separate. Perhaps the problem is just in our categorizing.

But there is a distancing in our relation to artworks; "Being made by human hands, the craft object is made for human hands...We look at the work of art but we do not touch it. The religious taboo that forbids us to touch the statues of saints on an altar -- "you'll burn your hands if you touch the Holy Tabernacle," we were told as children -- also applies to paintings and sculptures. Our relation to the industrial object is functional; to the work of art, semi-religious; to the handcrafted object, corporal....The handmade object is a sign that expresses human society in a way all its own: not as work (technology), not as symbol (art, religion), but as a mutually shared physical life." (page 20)

Is that true? I hope people who own artworks touch them; I do. It is only the museum protecting them from too many hands that keeps us separate. That is most of our experience of art, though, and may affect our relation to it in the way Paz says it.

And art is usually handmade; by "the handmade object" I think he means a handmade and used object, his definition of craft.

OK, industry. "Industrial design tends to be impersonal. It is subservient to the tyranny of function and its beauty lies in this subservience. ...Technology is international. Its achievements, its methods and its products are the same in every corner of the globe...(page 22). Craftwork, by contrast, is not even national, it is local. Indifferent to boundaries and systems of government, it has survived...Craftsmen have no fatherland: their real roots are in their native village...craftsmen defend us from the artificial uniformity of technology...: by preserving difference, they preserve the fecundity of history." (page 23)

I think he is talking about traditional craftsmen, not us. We influence each other all around the world, borrow freely from traditions, are interested in and rewarded for innovation. But we are locally based. I even find it odd to sell pots online, where people choose pots only by look, and cannot feel what they might be choosing. And a product of industry, however uniform, changes with different contexts of use. I once saw a set of photographs of those basic resin chairs, in settings all around the world. Wonderful variety, emphasized by the one object that links them. But, yes.

"Between the timeless time of the museum and the speeded-up time of technology, craftsmanship is the heartbeat of human time. A thing that is handmade is a useful object but also one that is beautiful; an object that lasts a long time but also one that slowly ages away and is resigned to doing so; an object that is not unique like the work of art and can be replaced by another object that is similar but not identical. The craftsman's handiwork teaches us to die and hence teaches us to live." (page 24).

I think he overdoes the differences among objects we place in these categories. But it is a clarifying and convincing perspective, to me, and lovely, and encouraging. Back to the potting wheel!

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

Sunday, August 20, 2017

Cooing over Chun Glazes

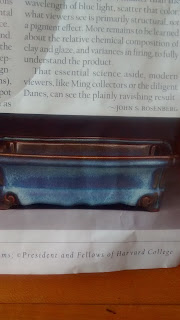

I love that look.

In the latest Harvard Magazine, there's an article exulting over their recent collection of pots in the original Jun glazes. The collection is a gift from Ernest and Helen Dane, the collectors, to the Harvard Art Museums.

These are the original pots, from the Song dynasty in China or a bit later. Fancy as they look, they are flower pots, for the emperor's palace, of course. The article says, in scholarly tones, that "Jun techniques in fact persisted much longer, at least into the Ming era (1368-1644)".

Actually we still make and fire these glazes, very happily, and usually spell the name "chun". Take a look at Pinterest or Etsy.

Aren't they wonderful?

I love the glaze. I'm not sure I love the pots. (Are we allowed to say that, about grand, historical marvels?) These 3 from the Harvard collection are published in the article. I find the long, rectangular piece wonderful, balanced, calm, beautiful. The others look chunky to me, which makes them seem heavy. And I have a hard time appreciating anything ornate, like the pot with saucer. My limitation, perhaps, not a less than wonderful pot.

In the latest Harvard Magazine, there's an article exulting over their recent collection of pots in the original Jun glazes. The collection is a gift from Ernest and Helen Dane, the collectors, to the Harvard Art Museums.

These are the original pots, from the Song dynasty in China or a bit later. Fancy as they look, they are flower pots, for the emperor's palace, of course. The article says, in scholarly tones, that "Jun techniques in fact persisted much longer, at least into the Ming era (1368-1644)".

Actually we still make and fire these glazes, very happily, and usually spell the name "chun". Take a look at Pinterest or Etsy.

Aren't they wonderful?

I love the glaze. I'm not sure I love the pots. (Are we allowed to say that, about grand, historical marvels?) These 3 from the Harvard collection are published in the article. I find the long, rectangular piece wonderful, balanced, calm, beautiful. The others look chunky to me, which makes them seem heavy. And I have a hard time appreciating anything ornate, like the pot with saucer. My limitation, perhaps, not a less than wonderful pot.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)